Macro 110

The big news today is Texas schools are closed for the year. This broke while I was writing this post, and I had to stop for a couple hours because I couldn’t focus. I knew it was the most likely outcome, but I was hoping we would get a week or two of some sort of adjusted system, anything. The next question is what to do about graduation, and none of the options are appealing. Zoom meeting? Mass email? Schedule it for August?

The good news is that Governor Abbott made Texas the first state to have a plan to move toward an intermediate stage on the way to fully re-opening the economy. I say good news because having a plan is better than not having a plan, in my humble opinion.

Definitely a downer heading into the weekend, but the show must go on.

If you were the government and wanted to maximize tax revenue, what is the best tax rate to do so? What percentage of individual income should you tax to get the most money, for example?

When I ask that question in class, I often see someone start to half-raise their hand and pull it down quickly as they realize their answer, (“100%”), is not going to age well.

If you tax someone’s income at 100%, they are not going to work in the first place. So a 100% income tax would result in a total income tax revenue of approximately $0.00. On the flip side, an income tax rate of 0% would also result in $0.00. So, we’ve narrowed it down—the ideal percentage to maximize revenue is somewhere in between.

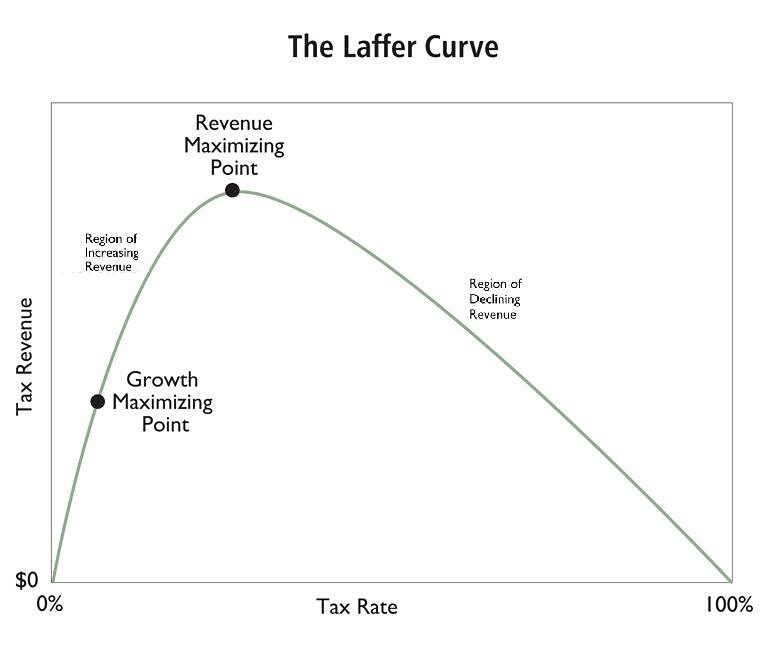

This seems obvious, right? But the core idea that, at a certain point, increasing tax rates will actually lead to decreasing tax revenue (and vice-versa), is somewhat counter-intuitive. This is demonstrated by The Laffer Curve.

Yeah I know, I’m getting fancy, putting a graph in the post, and this is clearly a *slippery slope*, but don’t worry, I’m a long way from including targeted ads every few paragraphs or putting my content behind a paywall.

I took that chart from an article at the Cato Institute. The article takes the counter-intuitive-ism to another level by questioning another assumption: when discussing tax rates, why is our starting point the goal of maximizing tax revenue? Is that the purpose of government? [no, the purpose of government is to provide pure public goods!] That’s why the graph has two points, because it’s arguing that tax rates shouldn’t be set to maximize revenue, but rather to maximize growth.

Enough philosophy, let’s be practical.

As of now, there are seven federal income tax brackets: 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, 37%. If your taxable income is from $0 to $9,875 (and you’re single/non-head-of-household), then you are in the 10% bracket and you will pay 10% of your taxable income to the federal government (this is not counting state/local taxes, or other automatic deductions I mentioned in the previous post). Note that I said “taxable income”. Remember the concept of a “standard deduction”? Taking the standard deduction automatically reduces your taxable income by $12,200.

So if your gross income is less than $12,200, you’ll owe $0 in federal income taxes. The other taxes you pay vary state-to-state, city-to-city, and so on. Here is a breakdown of state income taxes. You know how Texans are always complaining about how many Californians are moving here? Well, compare their state income tax rates. California has the highest marginal tax rate, at 13%, and Texas is locked in at 0%. You think that may be a factor?

Don’t get it twisted, state governments have to get their money somewhere, Texas just does it primarily through property taxes. In Texas, it’s standard procedure to file a “protest” with your local government each year to argue that your house is worth LESS than what they appraised it for, because it can mean the difference of thousands of dollars in taxes. I’ve done this, and it’s Kafka-esque.

I am fighting delving too far into property taxes, but this story is too interesting not to share: the Travis County government is not allowed legally to use third-party information to appraise property, which would be the easy and obvious way to determine taxes, and they were just found guilty of doing that exact thing. The Austin Board of Realtors called them out, and now Travis County is freezing all property taxes at 2019 levels because they don’t have the tools to assess it on their own.

Where was I? Look, it’s important to realize that taxes take many forms, the federal income tax is just one angle. Here, a wiki article entitled Taxation in the United States. See? I have to focus on federal income tax or this post will never end.

So, you know the seven brackets, and you know the concept of “taxable income” versus gross income. The next thing to understand is how the marginal brackets apply.

If your taxable income is exactly $50,000, how much do you pay in federal taxes? Refer to the brackets. That’s in the 22% range, so the initial thought might be $11,000, which is literally 22 percent of 50,000, but that number is far higher than you actually owe. As your taxable income goes through each tax bracket, it is taxed at that rate. Your first $9,875 is taxed at 10%, so you owe $987.50 on it, even if you made a billion dollars. The next bracket applies to every dollar you make from $9,876 all the way up to $40,125! For each dollar you make in that range ($30,249), you owe 12 cents (totaling $3,629.88). For your remaining $9,875 of income, your marginal tax rate jumps up to 22% (totaling $2,172.50).

987.50 + $3,629.88 + $2,172.50 = $6,789.88 owed in federal income tax.

The amount you actually end up paying in taxes is called your effective tax rate. In this case, you paid roughly 13% of the $50,000 in taxes, but recall that you also took the standard deduction, which means your gross income was $62,200. Your effective tax rate is what you paid divided by what you made, so 10.9%.

If you look at the highest bracket, 37%, it applies to every dollar you earn above $510,301. Remember when I said California’s highest marginal rate was 13%? Well, that bracket applies to people whose taxable income was over $1,000,000. If that’s you, you’re paying a full 50 cents of every additional dollar you earn—37 cents to federal taxes, and another 13 cents to state taxes.

Is that a lot? Too much? Not enough?

It depends.

[Side note: This proves that a penny saved is not equal to a penny earned. If you earn one additional penny, you have yet to pay taxes on it. If you save one additional penny, you have already paid the taxes on it. Saving more > earning more. #frugality]

The United States has a complicated history with taxes. I mean, we only exist because some people thought their taxes were unfair, right? This chart of the highest marginal tax rates in U.S. history shows that in 1944 and 1945, the highest bracket was 94%. By comparison, 37% seems agreeable. [Side note: clearly they were focused on raising funds for WWII then, but you don’t see similar increases in recent history, because politicians have learned that raising taxes hurts their re-election chances, so they would rather borrow money and increase the national debt and let someone else deal with it, literally passing the buck.]

What about other countries? It’s difficult to compare, because there are so many different approaches and a cursory glance won’t help much. I couldn’t find any sources that summarize it satisfactorily, so you’re on your own. I will say this, though: when you hear people on the TV saying “X country has this tax rate” or “Y country does it this way”, the reality is much more complicated than the sound byte and I can guarantee the talking head is ignoring any complications that would undermine his or her point.

It’s Friday, so I owe you a podcast recommendation. I think Choose FI (FI = Financial Independence) is great in general, and on their most recent podcast they unveiled a free 9th through 12th grade financial literacy curriculum. That’s awesome. I haven’t gone through it yet, but I trust them enough to say it’s worth looking into, if you’re curious. If you’re not curious, good luck out there!

Everything we just went through falls into the category of Fiscal Policy. The government makes the rules, and the rules matter, because people respond to incentives. Should we have a flat tax or a progressive tax? If progressive, what should the brackets be? What if we get rid of the income tax altogether, and have a VAT instead? What about capital gains tax? Sales tax? Hopefully, it’s clear the policies you settle on will not only affect government tax revenue, but also affect human behavior. That’s kind of the whole point, right? Once you start thinking about taxes as a “tool”, something to create the outcomes you want, then you’re trying to predict human behavior at the hundreds of millions level, and people are infinitely unpredictable.

This reminds me of one of my favorite quotes, by Freidrich Hayek:

“The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

This is where we discuss whether billionaires should exist, and I’m sorry to say I don’t have much to add to the conversation, because it’s a pointless question to ask. If we’re talking about an imaginary perfect world, sure, I support a 100% tax on personal wealth over, say, $500,000,000 (500M), especially if I was confident that tax revenue would go to my definition of pure public goods, but they wouldn’t need more funding in the first place, because, hey, it’s a perfect world, right?

In reality, if you have a billionaire tax, you know what will happen? They move. Thank you, next. I don’t want to type out John Galt’s speech in Atlas Shrugged or anything that extreme, but political rhetoric against “the rich” is short-sighted at best. The top 1% of income earners pay about 40% of the total federal income taxes nationwide. So, if you raise taxes too high on that group, they take their talents somewhere more understanding, and 40% of your income tax revenue disappears. What then, raise taxes on the new 1% to cover the difference? That reminds me of my favorite quote from Dodgeball, when Average Joe’s decides to forfeit and the announcer’s response is “It’s a bold strategy, let’s see if it pays off!“

If there’s one thing I know about the uber-wealthy, it’s that they care about protecting their wealth. They pay close attention to the tax code, by which I mean they hire accountants and lawyers and lobbyists to pay attention. In short, they know the rules of the game better than anyone, and tiny changes can lead to a complete 180 in behavior. A rule change you are completely oblivious to might mean the difference of millions of dollars to them.

Listen, I don’t love the existence of billionaires, and, okay, I bet some of them are bad people, and sure, there’s many who did little to nothing to earn their wealth and, yes, it’s tempting to pose hypotheticals like “if we take X amount from person Y just imagine the good we could do with it, while they would hardly notice it’s missing!”, BUT! Just stop. The United States has 585 billionaires, the most of any country, and that’s a good thing.

My advice is minimize the time you spend being upset that someone is richer than you, or smarter than you, or prettier than you, or whatever else you are tempted to be jealous and petty about, and spend more time making yourself better. Learning the rules of the game is a great place to start!

I do have thoughts on how capitalism’s “winner-take-all” system will continue to increase inequality and create new problems as the world economy globalizes (although maybe this virus will slow that trend?), and I am in favor of figuring out some sort of robot/AI tax and (if it works) maybe even using it to fund UBI, and things of that nature. So I’m not saying everything is great, nor am I saying there’s nothing we can do to make things better. I am saying the “eat the rich” mentality is self-destructive, full-stop. It cannot be the starting point in any healthy conversation about where we go from here.

I didn’t even get to how funny it is to see people talk about billionaires like they have a billion dollars sitting in a savings account. It is funny though, and if you don’t know why, then you should educate yourself.