Macroeconomics 101

What is unemployment, and what does it mean that 3.3 million Americans applied for unemployment benefits last week?

Pause. If you listen to one Economic podcast this week, make it this one: Coronavirus Economy Update: What’s Happening Right Now with Economist Tyler Cowen (on the James Altucher Podcast). I cannot vouch for the podcast, as I’m not subscribed, but that episode is quality, and Tyler Cowen vouches for himself. He’s been blogging for over 17 years at marginalrevolution.com.

If you don’t think about it, your first instinct may be that anyone without a job is unemployed. If you do think about it, it gets complicated quickly. Okay, the concept is still simple, you just have to divide the the number of “unemployed” by the “labor force”, and that gets you the unemployment rate. Defining those terms is where it gets tricky. To count as “unemployed”, you have to not have a job, actively be looking for work (within the last four weeks), and be available to start right away. To count in the “labor force”, you have to be at least 16, and either employed or unemployed. Military personnel and people living in “institutions” (jail, etc.) are not counted in the labor force. The nationwide unemployment rate is the result of a survey covering 60,000 households, around 110,000 people. The March unemployment data is scheduled to be published on April 17, and Texas is *projected* to reach near it’s all-time high of 9.2%. James Bullard, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, made headlines Sunday when he predicted national unemployments rates of 30% in the second quarter (April/May/June). As usual, these sorts of projections depend on a series of educated guesses based on variables that are impossible to pin down, but if they are close to being correct, it is way beyond sobering. Our recent “Great Recession” never had nationwide unemployment rates over 10%, and the Great Depression itself topped out about 25% nationwide.

Is unemployment always bad? It depends. Sometimes unemployment can be healthy for the economy, and it’s possible to be good for the person in question. “Structural unemployment” can be good for the economy, as it’s a sign of progression. For example, when cars were being phased in and carriages were being phased out, there were likely a lot of carriage-dependent workers temporarily out of a job, but it was, on the whole, good for the economy. “Frictional unemployment”, on the other hand, is due to individuals being between jobs. That’s not always bad for the unemployed worker! Maybe they finally had enough of their boss, or gave up on a dead-end job, or maybe they saved up enough to move to a place with better prospects. A healthy economy will always have some amount of Structural and Frictional Unemployment—can you imagine if the unemployment rate was 0%? That would be a nightmare, right? Everyone has the same job, forever! So, lower isn’t always better, when it comes to unemployment rates, and in fact there is an “equilibrium” rate of unemployment (aka “full employment”) for every economy, called the Natural Rate of Unemployment (NARU).

The third main type of unemployment is “Cyclical”. Everyone agrees this one is bad for the economy and for the workers who end up unemployed. Cyclical unemployment is the result of a contraction of the economy, and a decrease in demand for workers. That is what we are seeing right now. I know multiple people who were laid off or had to fire someone in the last week, and they weren’t even working in the sectors of the economy that look like they will be hardest hit. What sectors are going to be hardest hit? Starting with the obvious: anything considered non-essential! Tourism was the first to go, and now we’re at anything that requires crowds, or even in-person interaction. But, as we covered in the first quarter, everything affects everything else. If 3.3 million Americans filed for unemployment last week, then, theoretically, they will be getting unemployment benefits sometime in the not-too-distant future. Unemployment benefits vary state-to-state and job-to-job, but the national average is roughly 45% of their employed income (in the range of $300-400 per week), lasting for up to 26 weeks. The stimulus package is going to change that, and I’ll write about that tomorrow. What are the newly unemployed going to do with that money? With the future so uncertain, they are going spend that money differently than they would otherwise. Less of it is going to go toward entertainment or “luxuries”, and more will be unspent entirely (aka saved). If that many people filed for unemployment, think of how many people are out of jobs who don’t have that option. If you were a freelancer, or self-employed, you don’t have the option to file for unemployment because there is no company to file a claim with.

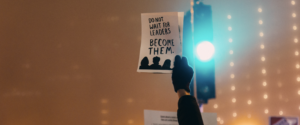

Understanding that a nationwide shutdown will result in a massive evaporation of jobs is basic economics. So why are we under orders to self-quarantine? Simple: our political leaders determined the costs of a shutdown were less than the costs of the other options. Costs and benefits are difficult to calculate, even more so on unprecedented scales that combine human values and economic benefits, and we are starting to see pushback as the lockdown extends. If you believe Brad Pitt’s character, Ben Rickert, in The Big Short (retelling and explaining the causes of the 2008 recession; R-rated primarily for language), we can expect 40,000 additional deaths for every additional percent increase in unemployment. I’m not going to attempt to verify or debunk that claim, mainly because those sort of statistics depends on which side you want to believe. The basic point is true: there are very real tradeoffs, human lives, at stake on both sides. It does resemble a war, in that regard, and the decisions we make will affect the outcome.

1 thought on “Unemployment”

Pingback: The CARES Act, Part 2 – Nathan McClallen